Franck de Chazal – Mayer

- Biographie par Jacques Dumora

- Great Uncle Frank de Chazal Mayer by Hamish Levack ( in English )

- Journal de Franck de Chazal-Mayer aux armées françaises.

Biographie par Jacques Dumora

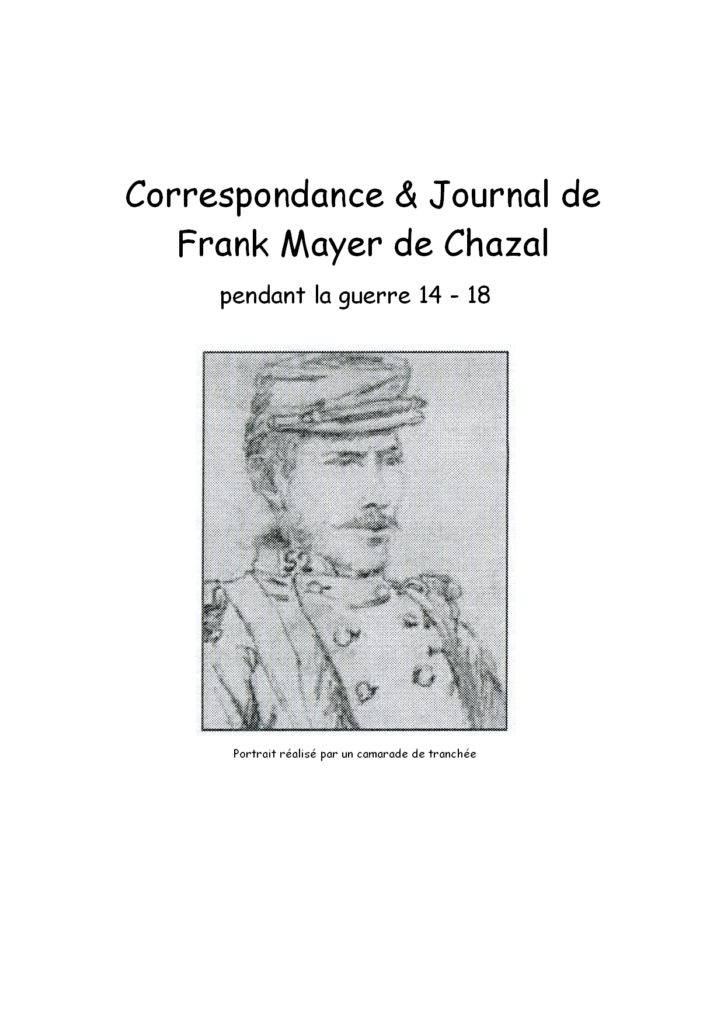

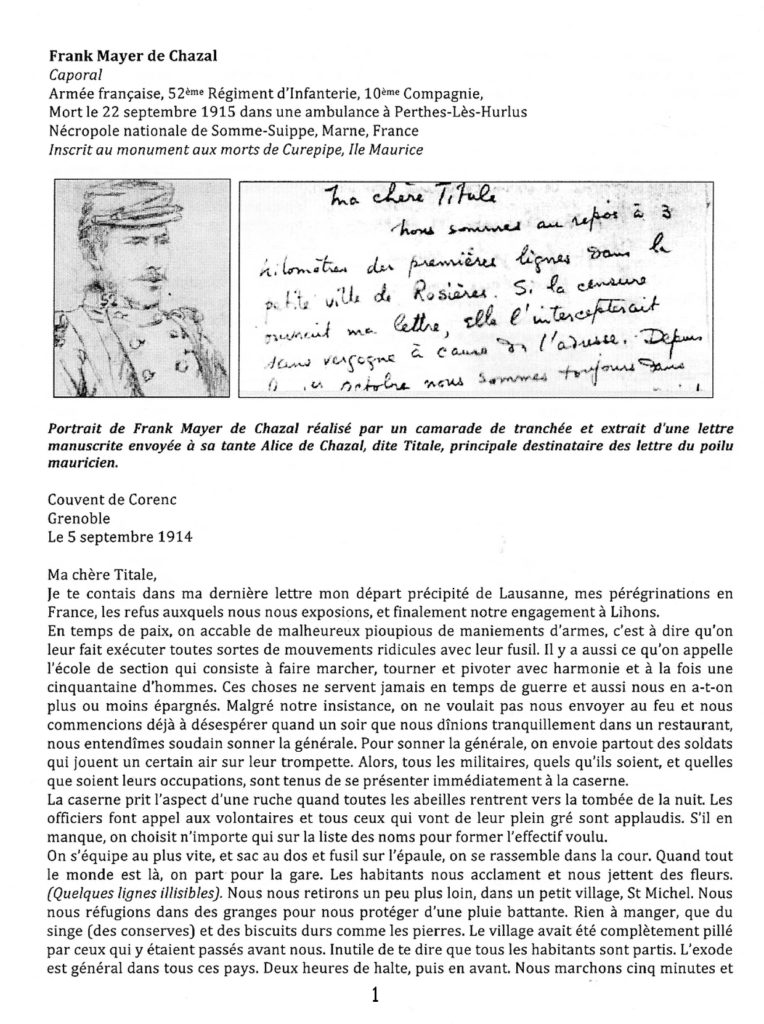

Né à Vacoas le 27 juillet 1891. Fils Georges Clifford Mayer et de Berthe de Chazal. Ancien élève du Collège Royal, il suit des études de chimiste agronome quand la guerre éclate. Il se présente aux autorités françaises pour engagement mais il est refusé. Il persiste en mobilisant les autorités préfectorales de Lyon et le consul britannique, et il est enfin recruté à la 10ème compagnie du 52ème régiment d’infanterie avec Fernand Antelme. A la fin du mois d’août 1914, il se bat dans les Vosges où il reçoit une blessure légère soignée pendant un mois dans l’un des hôpitaux complémentaires de Grenoble. A la veille de la bataille de Champagne, le sergent Chazal – Mayer est grièvement blessé à la tête et décède le 22 septembre 1915 à l’ambulance 16/14 à Saint-Remy Sur Bussy, dans la Marne.

Franck de Chazal – Mayer repose dans la tombe 2203 de la Nécropole Nationale < Somme-Suippes > à Somme-Suippes dans la Marne.

Première citation : < Engagé volontaire anglais pour la durée de la guerre, s’est fait remarquer par sa bravoure et son courage à l’attaque d’une tranchée allemande et a abattu quatre ennemis. >

Seconde citation : < Sergent d’une bravoure réputée. Est mort glorieusement pour la France, le 22 septembre 1915, des suites de blessures reçues au feu en faisant vaillamment son devoir. >

Tout au long de la guerre, il écrit à sa famille sur les conditions de vie dans la guerre et y renouvèle sa foi patriotique. Croix de guerre avec étoile d’argent

Texte de Jacques Dumora

Great Uncle Frank de Chazal Mayer by Hamish Levack

I have several interesting great uncles but the one that fascinated me most was my great uncle Frank Mayer. This is because several of his letters and sketches survive.

Like me, Frank was born in Mauritius, and won a scholarship to attend university in Britain, but in his case, it was Cambridge. In 1914 war was declared while he was on a cycling holiday in Switzerland. Worried that the war would be over before he had the fun of being in it, he decided to enlist in the fastest way possible, which meant joining the French army. At Lyons he was issued with the jaunty uniform that the French army began the war with, that also made them conspicuous targets – red trousers, blue coat with double rows of brass buttons, brown leather harness, long bayonet, and a kepi. From Lyons his regiment went to the Vosges where it engaged the advancing German forces. Frank was wounded and taken to a hospital in Genoble to recover. Later he re-joined his unit north east of Paris and was subsequently decorated with the Croix de Guerre for dispatching several Bosch while leading a section that captured a trench, but was killed himself on 21 September 1915.

Tante Alice, the aunt who had brought up Frank, kept the letters he sent her. By the 1980s, my uncle Thomas Mayer, was in possession of the first half of them plus some photos of Frank, and I had inherited some sketches from my mother that were drawn by Frank and his friend Vissier while they were in the trenches. Thomas translated the letters and made them into a book called ‘Letters from the French Front 3 September 1914 to 7 May 1915’. In his introduction Thomas says his book was prompted by the fact that his daughter, Juliette,

[my first cousin], took part in a school production, “Oh What a Lovely War” and that coincidently she had the same birthday as Frank. In fact Juliette not only had a great uncle in the French army, but also a paternal grandfather, [who was my grandfather too,] in the British army and a maternal grandfather who was in the German army. By trying to kill one another these soldiers were in effect trying, sometimes successfully, to preclude the future existence of their own off-spring, including me, and about half of my first cousins.

Thomas quotes his mother [i.e. my grandmother] Rita Mayer [née Hunter], who says her sister-in-law told her that Frank was killed instantly when he took off his helmet to wipe his brow.

However, in 2011, Mathilde Spall, [my uncle George Mayer’s daughter], copied me two letters written by a distant cousin, Margaruite Tuffier who lived in Paris in 1915, and one by Dr Gayet, the French army surgeon who witnessed Frank’s death. Contrary to the calming story that Rita had been told, Frank did not have a quick and easy demise. Shrapnel from an exploding shell struck his head and smashed up his legs, and he took two days to die. With the help of the Truffier/Gayet letters and the inter-net I was able to find that Frank had risen to the rank of sergeant, and was first buried in a cemetery called St. Remy-sur-Bussy, then in the 1920s was removed to a national necropolis at Somme Suippe, which is about 25 kms from Reims.

While browsing in a Wellington bookshop in 2013 I spotted a new book about WWI by a well-known author, Max Hastings. Probably he wrote the book called ‘Catastrophe – Europe goes to war 1914’ because he knew it would sell well, 2014 being the centennial year of the start of that war. Anyway looking at me from a photo in the book was great uncle Frank.

Max Hastings calls him François Mayer, and quotes him several times as giving a French soldier’s viewpoint. In the credits at the back of the book, Hastings refers to ‘Imperial War Museum’ [IWM] Mayer François’.

This recognition is due to my uncle Thomas who arranged for Frank’s letters to go to the IWM. At the time [1980] the IWM manager of documents wrote to Tommy saying “Your uncle’s descriptions of conditions in the trenches and his thoughts about the war, the French army and the German foe make the collection a rich source of information which is bound to be of value to many scholars in the course of their research”.

The famous Max Hastings was subsequently one of those scholars.

There is an epiloque. In 2014 while based at a Eurocamp in La Croix du Vieux Pont, Berny Riviere, Vic-sur-Ainse with my son Philip and his family we tried to find Frank’s resting place. Thanks to our car’s GPS and me being able to speak French to a Somme-Suippe villager we managed to find Rue General Leclerc and  the Necropole National but it was not what I expected. The internet had given me the impression that Frank’s bones had been piled into an ossuary. There was indeed an ossuary there, but his name was not on the plaque. However there were some 4000 well-marked and well-looked after graves, all with nice polished stone crosses and inscriptions, many of which referred to unfortunate French army soldiers who were killed in 1915 around about the time Frank met his death. Philip, Glenis, grandson Fraser and I ran up and down the rows of crosses in the rain looking for the surname ‘MAYER’, and were about to give up, not only because we were getting soaking wet, but also because it was time to take Glenis’s friend, Gillian back to Reims to catch her train to Paris, when ‘Bingo’ I found Frank’s grave. Photos were taken and jokes were made about how pleased Frank was to have what was probably his first family visit.

the Necropole National but it was not what I expected. The internet had given me the impression that Frank’s bones had been piled into an ossuary. There was indeed an ossuary there, but his name was not on the plaque. However there were some 4000 well-marked and well-looked after graves, all with nice polished stone crosses and inscriptions, many of which referred to unfortunate French army soldiers who were killed in 1915 around about the time Frank met his death. Philip, Glenis, grandson Fraser and I ran up and down the rows of crosses in the rain looking for the surname ‘MAYER’, and were about to give up, not only because we were getting soaking wet, but also because it was time to take Glenis’s friend, Gillian back to Reims to catch her train to Paris, when ‘Bingo’ I found Frank’s grave. Photos were taken and jokes were made about how pleased Frank was to have what was probably his first family visit.

Coincidently we visited Paris shortly afterwards, on 13th July 2014, which was the day before France’s main Bastille Day ceremony, and I was able to interact with the fellows who were dressed up as 1914 French army soldiers and were getting ready for the event. If I had been transported back 100 years in a time machine to talk to great uncle Frank, he might well have taken this photo of me.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.